Nick Dunn, Lancaster University and Paul Cureton, Lancaster University

Imagining future cities has long been a favourite activity for architects, artists and designers. Technology is often central in these schemes – it appears as a dynamic and seemingly unstoppable force, providing a neat solution to society’s problems.

But our recent research has suggested that we need to significantly rethink the way we imagine future cities, and move our focus from an overarching technological vision to other priorities, such as environmental sustainability and the need to tackle social inequalities.

We need to answer questions about what can be sustained and what cannot, where cities can be located and where they cannot, and how we might travel in and between them.

The coronavirus pandemic has further reinforced this need. It has profoundly disrupted what we thought we knew about cities. It has further sharpened existing inequalities and brought about major challenges for how we physically live and work together.

The future – yesterday

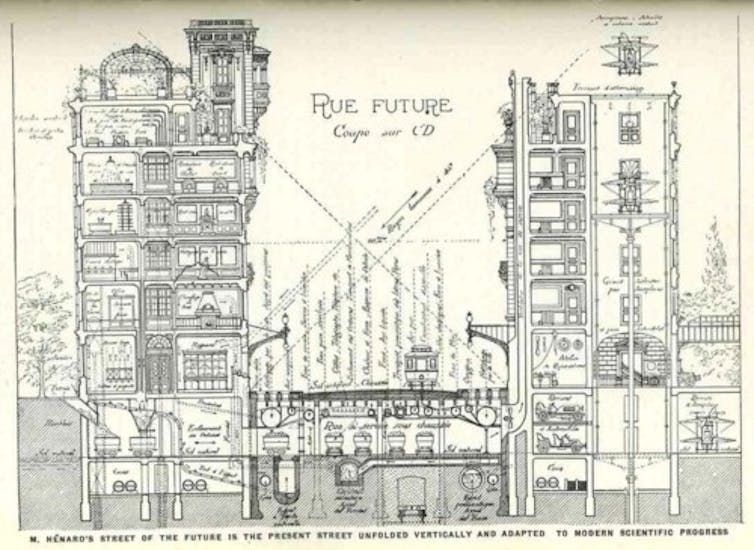

The architect and influential urban planner Eugène Hénard was arguably the first to publicly discuss “future cities” in Europe during his 1910 address to the Royal Institute of British Architects in London. His vision anticipated the technological advances of the future, such as aerial transportation. This approach, prioritising technology, was also evoked in cinema in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis.

|

|

|

It was also mirrored by architects such as Le Corbusier in projects such as the 1924 Ville Radieuse (The Radiant City). In this work, Le Corbusier developed his concept of the city as a symmetrical, regulated, and highly centralised landscape.Such an approach can be traced through many subsequent visions for cities, portrayed as the physical embodiment of technological prowess.

A new focus

But rather than simply focusing on technology to shape our future, we also need to look at it through social and global lenses. These alternative approaches are increasingly urgent. To provide a safe and sustainable world for present and future populations, we need to think beyond “solutionism”. This is the idea that every problem we have has a technological fix.

An identifiable shift in how future cities are being conceived, designed and delivered concerns the people involved in these processes. This ranges from localised projects to global initiatives. For example, the Every One Every Day project in Barking and Dagenham in London aims to make practical participation in neighbourhood projects inclusive and available to all residents. On a much wider scale, the New Urban Agenda global vision by the United Nations’ Habitat programme, meanwhile, calls for more inclusive and sustainable urbanisation and settlement planning.

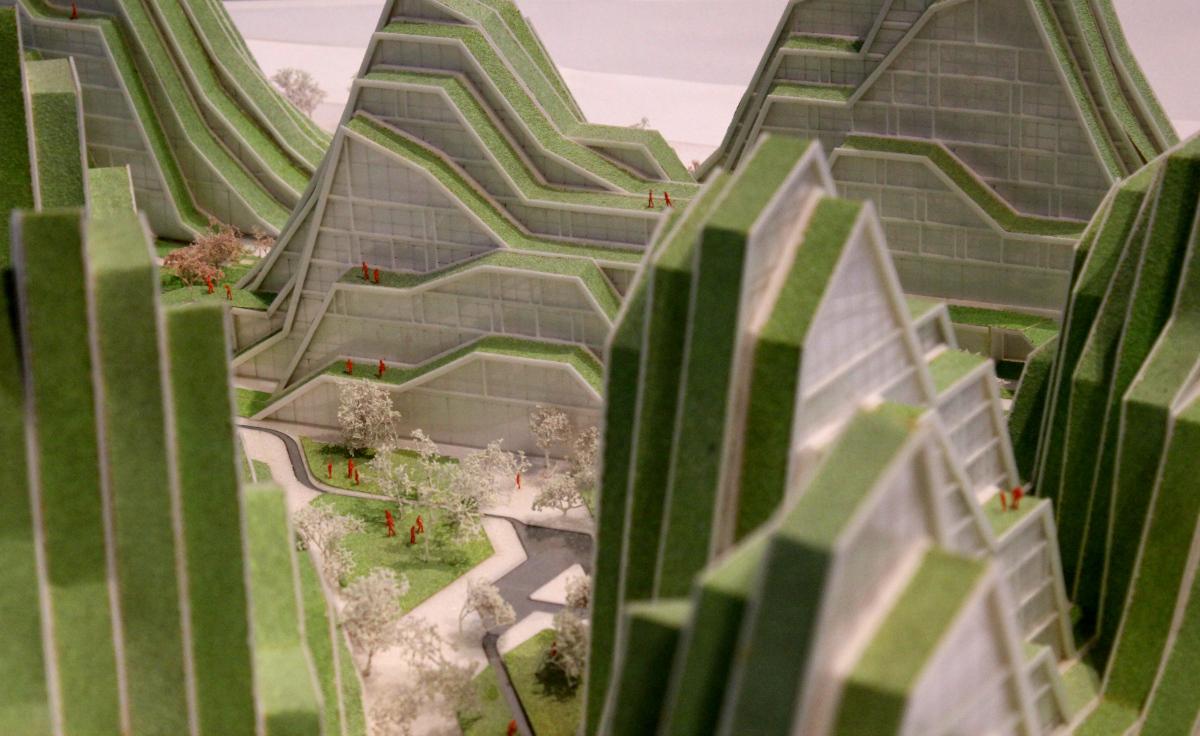

We may want our future cities to prioritise environmental renewal. The Green Machine, a design for a future city by architect Stephane Malka, moves like a mobile oasis, replenishing desert rather than causing more environmental degradation. This future city collects water through air condensation and uses solar power to drive itself over arid landscapes.

These are ploughed and injected with a mixture of water, natural fertiliser and cereal seeds as it passes. Agricultural greenhouses along with livestock farms support the city’s inhabitants and supplement local populations. The project is scaleable and replicable in relation to the number of people needed to be accommodated.

Climate change brings with it the possibility of dramatic sea level rise. Post Carbon City-State, a project by architecture and urban design group Terreform, imagines a submerged New York. The project proposes that, rather than investing in mitigation efforts, the East and Hudson River are allowed to flood parts of Manhattan.

The new city is rebuilt in its surrounding rivers. Former streets become snaking arteries of liveable spaces, embedded with renewable energy resources, green vehicles, and productive nutrient zones. This replaces the current obsession with private car ownership towards more ecological forms of public transport.

Both these projects emphasise responses to the impacts of climate change over technological innovation for its own sake.

Alternatively, the cities of the future may prioritise equality. This is illustrated by spatial design agency 5th Studio’s Stour City, The Enabling State.

This is a future city for 60,000 inhabitants, envisioned along the River Stour and the Port of Harwich in East Anglia, England. Based around the urbanisation and intensification of existing rail and port infrastructure, it features initiatives such as waste to power generation in order to support a viable, low-impact city, with priorities including affordable housing for all.

Imagining these cities helps us understand how we want our future lives to look. But we must open up the opportunity to conceptualise these futures to a wider and more diverse set of people. By doing so, we will be better positioned to rethink the shifts required to safeguard our health, that of other species and the planet we share. This is the significance of visions for tomorrow’s world – and why we need to create new ones today.

Nick Dunn, Professor of Urban Design, Lancaster University and Paul Cureton, Senior Lecturer in Design (People, Places, Products), Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.